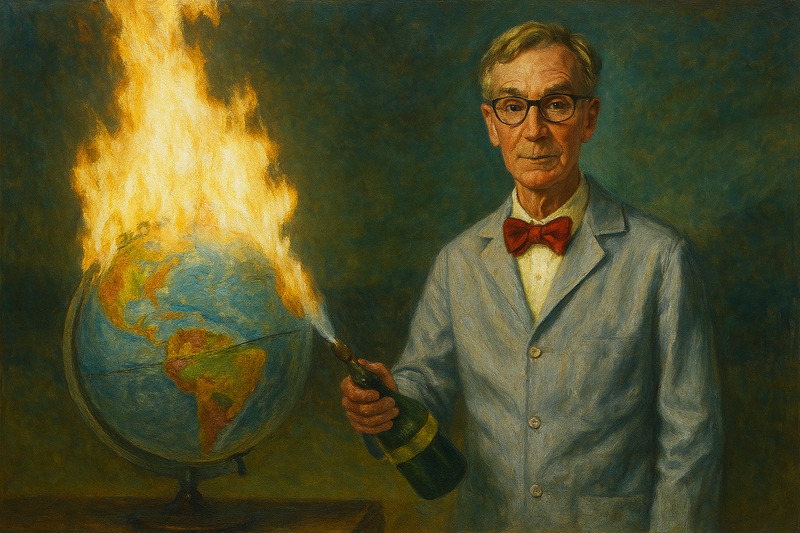

In a time of apparent crisis, truth becomes more than a virtue; it becomes a necessity. And yet, just when scientific knowledge is urgently needed, science communication has become increasingly vulnerable to distortion. The problem isn’t limited to misinformation from outside the scientific community. Increasingly, it includes well-intentioned exaggeration, oversimplification, and selective messaging from within—what some might call a “noble lie,” told in service of the public good.

This impulse is not difficult to understand. When faced with what some believe to be looming environmental catastrophe, political instability, or a disengaged and ignorant public, some communicators feel pressure to dramatize the facts: to sharpen the urgency, streamline the narrative, and provoke action. But in doing so, they risk compromising the very foundation of their authority: credibility.

Sometimes projections are presented without meaningful context. Sometimes confidence is emphasized while margins of error are de-emphasized. These moves are rarely malicious. They often emerge from institutional pressures—the need to communicate quickly, to align with policy goals, or to avoid public confusion. But they raise an enduring ethical question: should science communication aim primarily to persuade, or to cultivate understanding? The two goals are not always compatible. What persuades most effectively is not always what informs most honestly. Over time, that tradeoff can erode trust in both the message and the messenger.

This strategy rests on a consequential assumption: that the public cannot process uncertainty, that nuance will demobilize, and that open doubt might weaken support for evidence-based action. But that assumption is not only questionable; it is often counterproductive. When such simplifications are eventually exposed—and they frequently are—public trust suffers. In a fragmented information environment, credibility is difficult to restore. Once people suspect they’ve been misled, they begin to question not only the claims, but the process behind them. Even well-supported conclusions may come under suspicion. In the vacuum that follows, unreliable alternatives often take root.

Transparency is essential if science is to serve the public interest. But transparency alone is insufficient. A public that cannot distinguish between confidence and consensus, or between a single study and a robust body of evidence, will struggle to evaluate scientific claims on their merits. What’s needed is something deeper: a basic form of epistemic literacy. This does not mean universal technical expertise. It means cultivating the ability to recognize the structure of scientific reasoning—how claims are tested, how uncertainty is handled, and how consensus is (or is not) built.

This matters because scientific expertise increasingly influences decisions that shape everyday life: from environmental management to technological development, from health guidance to economic policy. When the public lacks the ability to interrogate expert claims, accountability becomes nearly impossible to achieve. In such a system, decision-making shifts toward expert-driven processes and away from public deliberation. The result is not always technocracy in a strict sense, but a civic environment in which many feel excluded from meaningful participation.

This leads to a difficult question: who holds experts accountable? Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?—who watches the watchmen? It cannot be left to self-regulation alone. Nor can it rely on automatic public deference. The only sustainable answer is mutual responsibility: a public willing to ask serious, well-informed questions, and a scientific establishment willing to answer them candidly, including, when appropriate, with “we don’t know.” This relationship is fragile. It can be damaged by institutional defensiveness, by rhetorical overreach, or by the temptation to simplify complexity for the sake of narrative coherence. But it can also be repaired and strengthened when both sides recognize that science is not a catalogue of conclusions, but a method of disciplined inquiry. It demands rigor, but also humility.

Honesty in science communication is not a tactic. It is a form of respect: a signal that the public deserves the full picture, not just the parts deemed actionable. It affirms that the role of science is not to persuade at all costs, but to clarify what is known, to contextualize what is uncertain, and to acknowledge what remains unresolved. In an era marked by rapid change and frequent public uncertainty, the stakes are too high for selective messaging. If science is to inform public action rather than simply guide elite consensus, it must be trusted. And if it is to be trusted, it must be honest.

The goal is not merely to inform the public, but to empower it. That begins with a commitment to clarity and the discipline to say only what can be known. Science cannot thrive on persuasion alone. It must rest on honesty, on limits acknowledged, and on the recognition that truth is not always convenient or complete. That recognition is not weakness. It is integrity—and it is the only foundation strong enough to support lasting trust.

Geoffrey Farmer

gkfarmer1983@gmail.com